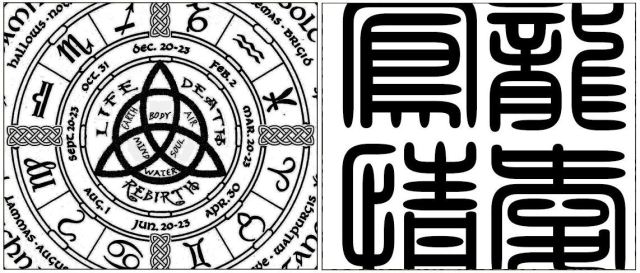

Left image of pagan Wheel of the Year from Biblical Connection.

Right image of a Taoist Fu sigil.

I don’t have educational degrees that would qualify me to write about any of this, so please understand that I am writing my observations within that non-expert context. Lately I’ve been fascinated with pagan and neopagan belief systems, mostly for how strikingly similar paganism is to Chinese Taoist-based folk religion.

Here’s how I understand paganism in context: Back in the day across Europe, Abrahamic religions rose to dominance, became institutionalized, and began setting up centralized bodies of authority that often started in the cities and spread its influence from there. At the fringes of the countryside, however, pagan faiths endured among the minority. These pagan faiths were polytheistic, though pantheist, strongly nature-based, and because they believed that everything was connected, it was thought that certain herbs, incantations of words, ritualistic conduct, and representations of elements could be harnessed to manifest intentions–in other words, magic exists.

Replace a few specifics from the previous paragraph and you could apply it to the relationship between Confucianism (and to a great extent Buddhism) and Chinese folk religions. These folk religions were looked upon in the same way pagan faiths were looked upon by the Christians. Those who practice pagan/neo-pagan religions (like Wicca, Druidism, Heathenry, or some form of pagan reconstructionism) tend to keep their faiths concealed or strictly private. That’s less of an issue among those who practice Chinese folk religions, and so you’ll see altars set up in Chinese businesses that still pay homage to the faiths of their [often agricultural] ancestors. However, like what pagans experience, those who still practice Chinese folk religions are considered fringe.

Sainte Chapelle Church Paris alcove. Source: Zorger.com

Since Abrahamic faiths are monotheistic and pagan faiths are polytheistic, the ideological tensions between the majority and minority in the West are greater. In China and most Chinese-dominant cultures (I’m thinking Taiwan and Hong Kong), the majority and minority are both polytheistic but pantheist in view, so there may be less of an ideological tension and more of a social class or status distinction.

[And by pantheist here I mean that these Eastern faiths tend to believe that the deities and all of us are interconnected into a greater collective immanent divinity. It’s really not that different from monotheism, except rather than see the one true God as a separate, independent entity beyond us, these pantheist faiths see God as all-encompassing. Everything around us including our Selves is part of God. The collective “us” is God. One is all and all is one.]

Another interesting note: When Christianity was first integrated into China by Western missionaries, the term Shang Di was borrowed from the folk religions and used by the missionaries to denote the Christian God. Prior to that borrowing, Shang Di already had an identity, as the Heavenly Father. I might compare him to Zeus, a leader of sorts among the many deities. That’s right, many deities. I believe that early Christian missionaries mistook the concept of Shang Di and per their conception, adopted the word to denote the one Christian God. Hence, today when we say Shang Di, we think of the Christian God as opposed to the traditional Heavenly Father of Chinese folk religion. (I’ve heard that pagan/neo-pagan practitioners, too, take issue with how Christianity has integrated various pagan practices and holidays into Christian culture to the point where now, the popular mainstream views those customs as strictly Christian and have forgotten about these customs’ pagan heritage.)

Arising from a pantheist view came the practice of magic or energetic workings. Since everything has spirit energy in it and there are different functions of different spirit energies, every aspect of the material world had a corresponding spiritual component that could be utilized with intention to make magical things happen.

Here’s another interesting similarity. I’ve heard pagan practitioners emphasize the distinction between Wicca and witchcraft. Wicca (again, only as I understand it, and what do I know) is a faith, but adhering to the Wiccan faith doesn’t mean one practices witchcraft. Witchcraft is essentially the practice of magic and energetic workings, believing that our lives consist of elemental energies related to the environment around us and these energies can be engaged in such a way as to positively or negatively influence our lives. I hope no one gets offended by me using witchcraft and ceremonial magic interchangeably here. Please believe me, I know that it isn’t, but I’m not writing an academic or historic treatise here. The point is ceremonial magic is distinct from the faith, though sure, most of the faith will in turn practice witchcraft or ceremonial magic.

I bring that up because it’s the same with the folk religions. Many of the Chinese agricultural-based communities will subscribe to some sect or lineage of folk religion and it is often eclectic, a mix of local spirits and sub-deities, plus iconography borrowed from Taoism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. They venerate the particular deities of their faith and partake in the customs and religious practices of that faith, but they aren’t necessarily engaged in the practice of magic. Then you’ve got Taoist priests and others who seriously practice Taoist-based magic, cast spells, dabble with alchemy, believe in the metaphysical significance of the moon and stars, and, of course, tell fortunes. Like the distinction emphasized by pagans between Wicca and witchcraft, there is a similar distinction here between the Chinese folk religions and Taoist-based ceremonial magic. That said, the reason they often get confused is because typically those of the faith will also practice the magic.

Christianity, which is the majority faith subscribed to in the West, generally frowns upon ceremonial magic and to enforce their notion that magic is bad, they vilify practitioners of ceremonial magic. Buddhism in the East may frown upon ceremonial magic, but it does not vilify its practitioners. Buddhism and what I’ll refer to as the Chinese proper society, or those who consider themselves enlightened and educated, look down on the folk religions and view such practices as the superstitions of the backward bumpkin. I don’t know which is worse or if there can even be a comparison–demonizing pagan faiths or looking down condescendingly at Chinese folk religions, one just saying “you’re stupid” while the other accuses you of being evil, but it is one way the two cultures differ.

(Oh, but after the Christian missionaries came into China, things changed. Chinese Christians would demonize the folk religions, and it didn’t help matters that most of these folk religions and their magical practices liked to incorporate red, which somehow justified the Christian assumption that these folk religions were demonic…)

Now, back to the folk religions. These folk religions come in a variety of forms and differ from region to region, each with their own local spirits and preferred deities for primary worship. A couple of the “big name” deities: there’s Tu Di Gong, for example, an earth-based deity popular among agricultural communities; Guan Gong, a great warrior who was later deified; Matsu, a mother-figure goddess of the sea worshipped by many fishing communities in the south; and Lei Gong, the god of thunder and a punisher. Practitioners of Taoist magic often invoke Lei Gong for vengeance-seeking or punishing intents. There is also speculation that Lei Gong is a repackaging of the Garuda from Hindu mythology. Kuan Yin, borrowed from Buddhism, is also typically venerated by various factions of the folk religions, especially by women.

Again, that is barely scratching the surface of the deity hierarchy. Beyond what I’ve named, there is an unaccountable number of lesser deities and spirits that are specific to a particular province or region in China. The spirits of ancestors can also be invoked. Like paganism and neo-paganism in the West, these Chinese folk religions are diverse and difficult to summarize with absolutes. Taoist-based ceremonial magic also cannot be defined, because there are countless lineages and each lineage will have its own rituals, approach and style to energetic workings, etc.

However, now in the 21st century, there has been a revival of these Chinese folk religions among the highly educated who (1) find it to be a comforting tie back to their ancestral lineages, and (2) find the pantheist, eclectic, nature-based approach to be more appealing than a dogmatic, institutionalized form of religion. (Does that not sound like some reconstructionist schools of paganism?) There has also been a revival of Taoist-based ceremonial magic, much like witchcraft and ceremonial magic among the pagan communities.

In Taoist-based ceremonial magic, elaborate rituals are conducted that involve altering the physical senses from ordinary experiences, meaning certain incense is used, special ritual objects, sacred utterances in old languages in rhyme, special clothing, and manipulating setting in a way as to alter participants’ consciousness. Sacred space is important, typically an altar, which is set up to face a specific cardinal direction, though which cardinal direction will vary from lineage to lineage. Front and center will be a statue, image, or likeness of the deity or deities venerated by the magic practitioner. Candles flank both sides, incense is in the center, and in front of the incense, the offerings. To either side may be knives or daggers of particular spiritual significance, bells, divination blocks, and other paraphernalia. Water used needs to be consecrated. The timing of particular rituals is keyed to lunar phases and astrology.

Practitioner’s notes on altar set-up in one Taoist-based lineage of ceremonial magic.

And in case you got confused there for a minute and thought I was still talking about Western paganism, oh no, I’m talking about the Taoist-based Chinese folk religions and their magical approaches. Strikingly similar, isn’t it?

The similarities keep on going. Many pagan/neo-pagan practices include a ritual knife they call an athame. Many Taoist practices include a ritual knife or sword used to manipulate unseen metaphysical energy believed to be present during a ritual or it can be used to cut through malevolent energies and clear a sacred space. Pagans/neo-pagans incorporate tarot into their practice. Taoist practitioners are into the I Ching. Both East and West ceremonial magic practitioners are into alchemy of one sort or another. The alchemists of both cultures are on a quest for immortality and started off in the early days with experimentations using lead and mercury.

Left image source: Three Hundred and Sixty Six, “Faustus in the Magic Circle.”

Right image source: Chi in Nature (Taoist Master) Blog, Taoist-based ceremonial magic altar.

Many pagan faiths cast a circle before commencing a ritual. The spiritual energies they believe in are then invited or called into the circle. In these Taoist-based folk practices, the setup of the altar is important. In many lineages, the practitioner has a seal that is likened to a key for connecting the altar to the spiritual world. The key must be present to activate the altar and open the so-called portal into the unseen realms. Certain words have to be uttered and particular gestures or ritualistic movements are incorporated.

Source: kaiselin from the China History Forum

In the majority of pagan practices, it’s my understanding that after casting a circle, the four quarters are called, or Watchtowers where the four guardians of the four cardinal directions are evoked. That’s crazy! Taoist-based practitioners have that, too. They’re referred to as the four guardians: the Black Tortoise in the North, the Red Phoenix in the south, the Blue Dragon (some lineages say the dragon is Green) in the East, and the White Tiger in the west. In some magical lineages, the four guardians aren’t referred to by totem animals, but rather as minor deities. Also in Taoist-based ceremonial magic, both the circle and the pentagram are significant. The circle represents the cycle of manifestation among the five elements (Wu Xing) while the pentagram represents the cycle of transformation.

Wu Xing: Cycle of Manifestation & Cycle of Transformation

Today with all the cultural cross-pollination that goes on, it is even more difficult to determine what comes from where. A lot of the practices I hear Wiccans perform around the house during their sabbats sounds a lot like feng shui to me. Using a special broom exclusively for “cleaning” negative or stagnant energy from a room by sweeping it back and forth in the air, taking care that it never touches the floor? Maybe we don’t use a broom exactly, but that’s feng shui. We might opt for bells or wood blocks.

Paganism consists of a great variety of traditions. Likewise, Chinese folk religions cover a diverse spectrum of belief systems. They don’t have one identifiable sacred text like the Bible, the Torah, or the Koran. They’re polytheistic, yet pantheist, believing that at the heart of matters, we are all one. Because of that belief in oneness, there is a strong veneration for nature, since natural forms contain components of Spirit and that Spirit can guide and empower us.

It would be an incredible and enlightening exchange if a panel of pagans and a panel of Chinese folk religion practitioners could get together and open up dialogue. I tried to find some information about such a convergence but didn’t find any. If any of you out there know more than I do, please share.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I found this board and

I find It truly useful & it helped me out a lot.

I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

LikeLike

This is very interesting. I am a Westerner, and I was brought up Christian, but then I practiced Wicca for a while. Then I seriously practiced Taoism and Zen and eventually became a teacher. The past few years, I have been revisiting the Western pagan practices again and now incorporate all of it. Wicca and Buddhism seem to be the foundation. This was a nice, simple introduction to the similarities between the two and they certainly are there, much more than we know.

LikeLike

I have just discovered your blog today after purchasing The Tao of Craft. I am extremely excited to have found your work and I’m sure my practice will benefit greatly from it. Please check out this blog when you have a chance, I have a feeling you will enjoy it : http://sarahannelawless.com.

LikeLike

As a Sarawakian Chinese I feel a need for the folk spirituality to be preserved or at least documented for posterity. Logically thinking it is under constant threat from being swallowed whole by Buddhism. Yet the reality speaks differently as any partake in the related annual festivals reveal the traditions as being vibrantly alive and well.

The trickiest past here is our national registration system. Our identity cards contain a section for religion and all Chinese from Temple-going families are automatically given the title ‘Buddhist’ without considering exactly what temples they are visiting. As a result, a process happens in many of us where in our early days we visit CFR(Chinese Folk Religion) temples(either exclusively, or alternating with pure Buddhist temples) as kids because our elders did so; later in life we decided learn more about our religion, as stated on our name cards, and start to wonder 1.) Why isn’t Buddha featured in some temples 2.) Why aren’t certain deities like the Hokkien Patron Deity, and Great Uncle Deity, as well as some local(SE Asian) Deities listed in the Buddhist(mahayana) pantheon? 3.) If Buddhism is a philosophy free from superstition(especially theravada. Btw for the difference between T and M just use Google) why do so many of us pray to Deities? Thus we either turn to books or some senior Buddhist for answers. Then, besides being educated on Buddha’s teachings we are taught that CFR(note that in Chinese conversation there isn’t really a word for CFR) is an inferior practice, mere superstition. If the source was Mahayana we are also told that the Bodhisattvas are superior to both Chinese folks deities and Taoist Gods.

I’m not interested to debate which practice is better but I just think my race esp those where I come from need to know that CFR isn’t an inferior, superstitious, and misled part of Buddhism, wherein Buddha’s teachings await those who are more ‘intelligent’ to ‘upgrade’ to, but a separate albeit syncretisable path with different characteristics.

Outside this country there are those who think that CFR is Taoism but I believe that the former predated and was later to some extent absorbed by the latter, which is at its purest mostly philosophy.

I myself grew up practicing CFR and later became one of those Buddhists who look down on CFR. I later had the opportunity to explore several different faiths in depth. After years and years I realised my disinclination from dogma and my conviction that morality is a living, evolving principle. CFR has very little philosophy beyond 1.) Go to Temple every now and then 2.) Celebrate Lunar New Year 3.) Celebrate various occasions such as the birthdays of the Deities(just last night the birthday of Kong Teck Choon Ong was celebrated with great splendour. This event was gazetted by former colonist Brooke after his own mystical experience with it) 4.) If troubled and so inclined seek the advice of a temple medium. Here lies an optional, seemingly direct connection to the spiritual realm.

It can be summed up that we are given festivals to gather and have fun, and beyond that everything else is left to our own common sense. Funny how it took me so many years to see the beauty in this.

LikeLike

Pingback: Práticas Pagãs e a Religião Popular Chinesa – Colégio Platinorum

Pingback: Episode 150 – Tarot and Taoist Magic with Benebell Wen | New World Witchery - The Search for American Traditional Witchcraft