In my video “Taoism: A Decolonized Introduction,” I made a passing reference to the Six Ancestral Sage Kings (or Six Holy Kings) and their significance in Taoism, promising that I’d dedicate a standalone video on the subject, so here we are.

Everything you need to learn about the Tao can be learned from the Six Holy Kings – or so goes an axiom credited to Confucius.

He isn’t the only one to uphold the Six Kings as the paragon of aspirational virtue and wisdom. Even Confucianism’s rival school of thought, the Mohists, would name-drop the Six Kings, 堯舜禹湯文武.

Cultural references to the importance of the Six Holy Kings continues well into the modern era with the founding of the Republic of China. Sun Yat-sen cited the importance of the new Republic upholding the tradition and values of the Six Holy Kings (“中國有一個道統,堯、舜、禹、湯、周文王、周武王、周公”).

Chinese historian and philosopher Li Zehou 李泽厚 notes that the Six Holy Kings are shamanic rulers, wū 巫, and that their divine right to sovereignty comes from their alignment with Heaven, which is received on the basis of their abilities to commune with Heaven. The shamanistic-historical traditions of the Chinese civilization comes straight from the Six Holy Kings. (You can read more about this in Chapter 10 of I Ching, The Oracle.)

This companion blog post to the video is content I ended up taking out of the video script, because it was getting really long and boring. =)

Holy Kings 聖王

The Six Kings Yao, Shun, Yu, Tang, Wen, and Wu are called “sheng wang 聖王,” which translates to Holy Kings or Sage Kings. They span san dai 三代, the three founding dynasties of the Chinese civilization. It’s implied that they are ancestral kings, which is to say they are venerated as one would venerate ancestors.

The Tao Te Ching (TTC) makes references to “sheng ren 聖人,” with that same character “sheng 聖.” TTC verses present axioms on what it means to be a sheng ren, an immortalized sage, an ascended master, comparing their saintliness and virtue to the mundane or profane. Ren 人 means people, humanity, and can refer to the subject in its singular and its plural form.

Thus in context, sheng wang 聖王 would be the reigning kings of the sheng ren 聖人, which I translate to the awakened ones. In other words, to become an awakened one, follow the guidance and traditions of the holy kings.

Sacred Significance of the Six 六

What is the most sacred power number in Taoism?

It’s six. Six is the most sacred power number, divisible by both the binary and the trinity, multiple of the twelve and 360 degrees of the circle and the cycles of our sun, moon, stars, the exponentiation of 6 squared is 36 for the decan rulers (the basis for the lunar-solar calendar), representative of the cyclical Way of the Sun, Moon, Stars. Likewise, the eight trigrams (fundamental building blocks of the universe) are doubled, 8 squared, to become 64, as in the 64 hexagrams of the I Ching, the cyclical Way of Change. Here, Way = Tao.

By the way, it’s cool to note that the three numerical values that are of greatest significance to Taoist mysteries are 6, 8, and 10, which also happen to be the Pythagorean triple.

Oh, and 6 is the smallest perfect number in mathematics, meaning it is the sum of its proper divisors 1 (unity of Tao), 2 (the yin-yang binary), and 3 (the holy trinity), giving it a particularly unique quality in numbers theory. One of the beautiful attributes to Taoist mysticism is the how it maths.

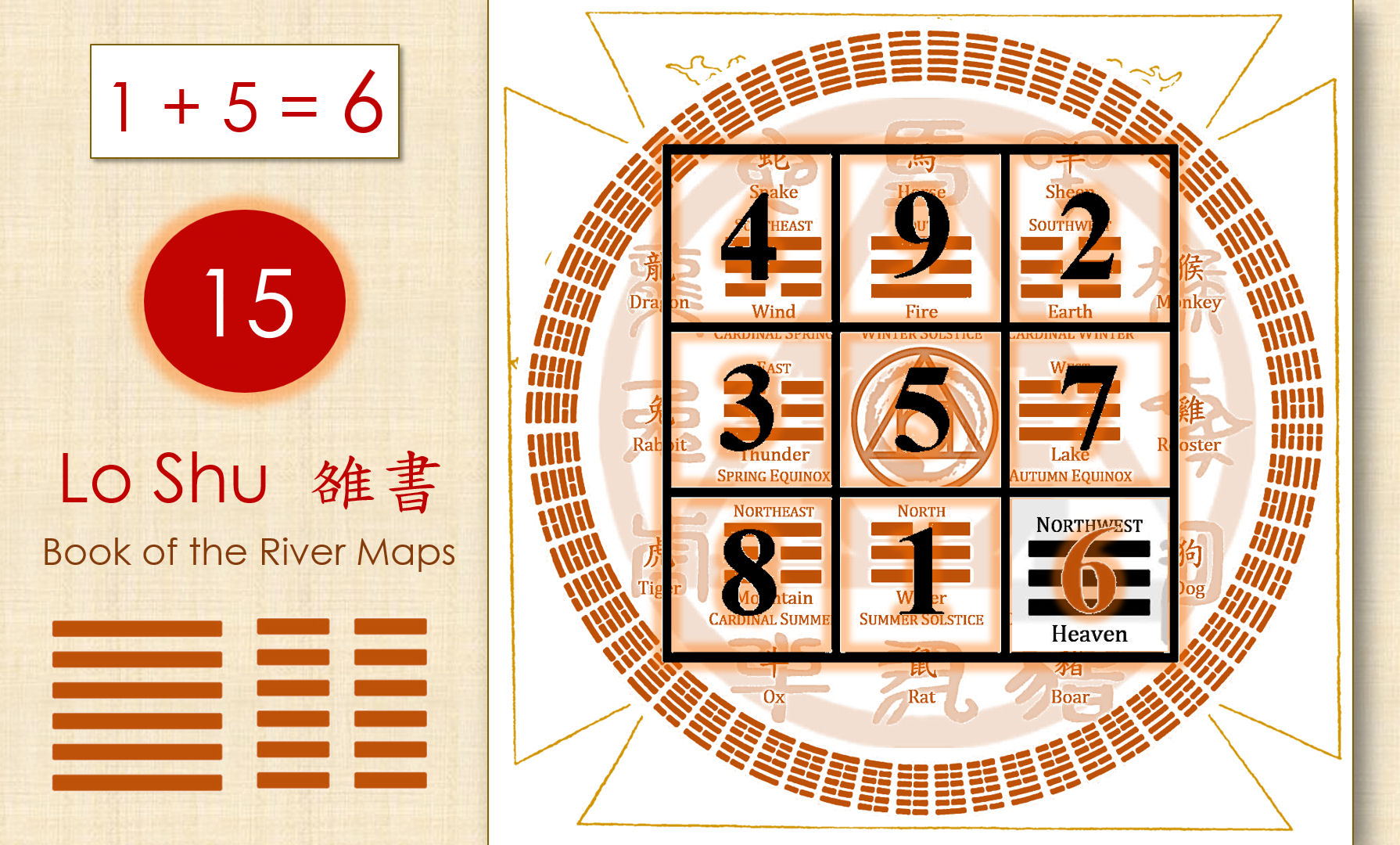

Note also how the Lo Shu magic square sector 6 corresponds with the trigram Heaven.

Here’s that line from the Secret Book of the Three Sovereigns 三皇内文遗秘 on the six powers of yin and yang alchemical or occult operation:

内隐阴阳六化之功,使修行之人,不遭外患。

The six inner powers 六化 achieved from these yin and yang methods [occult arts] are encoded within this Book;

May those who cultivate these [six] powers never suffer from external strife.

And here’s a meaningful passage from Jing Fang’s Commentaries on the Yi (I Ching), circa 77 – 37 BC, quoting from the Ten Wings of the I Ching:

言日月终天之道,故《易》卦六十四,分上下,象阴阳也。

The ideogram “Yi 易” itself represents the sun and moon, implying the cyclical movements of change of the sun and moon. Likewise, the 64 hexagrams are made up of an upper trigram and a lower trigram, like yin and yang, like the sun and moon.

八卦分阴阳,六位五行,光明四通…

The Ba Gua eight trigrams are eight categories of movements of yin-yang combinations, which occupy the six positions of the hexagram, moved there by the Wu Xing five elements (phases), all in motion because of “guang ming 光明,” a Light of splendor [there’s resonance here with Eliphas Levi’s Astral Light, which he notes is what magnetizes the movements of the world].

天地若不变易,不能通气,五行迭终,四时更废,变动不居,周流六虚。

Without that “guang ming 光明,” or Astral Light, there can be no Change. For it is that Light that energizes the seasonal changes, of Space and Time, through the Wu Xing five elements, through the six hollows of the hexagram (the Six Akasha 六虛).

There’s a lot of resonance here with Western occultism. For instance, Eliphas Levi corresponds the value six with the Magical Equilibrium, and that six is the hypothesis of God, and that enveloped within that Astral Light is the “two-fold vibration” balanced by the six.

On the Received or Lineaged Tradition (道統, Dao tong)

I mentioned the connection between lineaged traditions and orthodoxy with the Six Holy Kings, but in the interest of time, didn’t flesh it out as much as I’d like. Here’s more of what I had wanted to say about it.

In Doctrine of the Mean [中庸章句序], Song dynasty philosopher Zhu Xi 朱熹 makes reference to Dao tong, the received or lineaged tradition of the Tao, based on the axiom attributed to Confucius about the Six Holy Kings, i.e., all that there is to know about the Tao is embodied by the Six Kings Yao, Shu, Yu, Tang, Wen, and Wu. And so the principle of received, lineaged tradition and the Six Holy Kings are tethered.

While Dao tong is more often found in the context of Ru philosophy (Confucianism), it’s also used, in a slightly different context, in the Taoist Mysteries. It’s this idea that occult knowledge must be received through a system of transmissions that begins with Heaven. And so, for instance, the solution for how to tame the Great Floods was received by Yu the Great; the I Ching divination was received by King Wen, the line text was received by the Duke of Zhou, and so on. You continue to find that type of phrasing in other aspects of Taoist mysticism as well, where certain texts in the Taoist canons are characterized as having been received by their respective lineage’s prophets.

Pingback: 道教六聖王之謎 – benebell wen - FanFare Holistic Blog