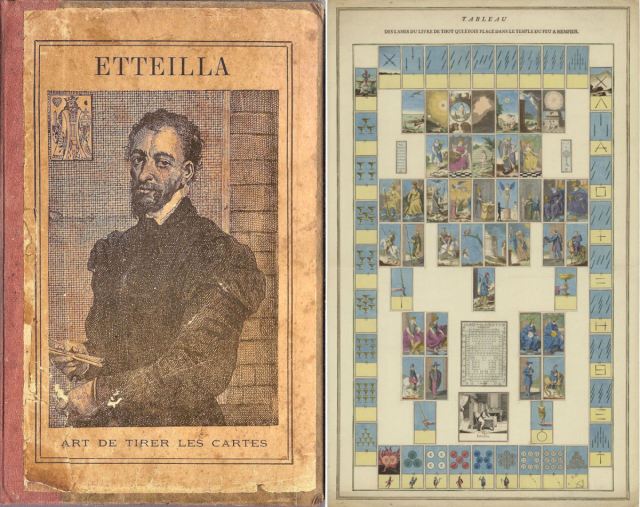

Cover of Le Grand Etteilla ou l’Art de tirer les cartes (1900s) and Livre de Thot Engravings by Pierre-Francois Basan (late 18th c.)

“It is impossible to imagine a physical means simpler or more natural than cartomancy, if one wishes to account for the extraordinary way in which the events of human life are linked together.”

– Etteilla’s “Épître à Monsieur Court de Gébelin” (1784)

ABOUT THE ETTEILLA:

We often hear about how the tarot community considers Jean-Baptiste Alliette (1738 – 1791), better known by his pseudonym Etteilla, to be the first professional tarot reader. Or at the very least he’s credited with having popularized the profession of tarot. But I had no idea to what extent he really was a bona fide 18th century tarot influencer.

An homage to him, in this brave new Post-Internet world of Instagram witches, the Tarot YouTube or “TarotTube” network, TikTok horoscope readings, and Facebook groups of tarot history aficionados just made sense. And that’s what my forthcoming Etteilla is– a redux of what he created, as a tribute to the first tarot influencer.

Not only did Etteilla do tarot readings for a living, he ran a magic school that he founded, which he called the New School of Magic. He advertised his tarot courses in local papers and taught people how to “go pro” with cartomancy. Many of the pupils who took tarot and divination classes from him went on to become tarot and divination teachers at his school.

Etteilla claims to have learned tarot at the age of 19 (the year 1757), taught by an elderly Italian cartomancer from Piedmont. He also propagated the belief that the tarot, known as the Book of Thoth, was a book engraved in hieroglyphics by the first Egyptians, and that mystical ancient knowledge was enshrined within. This Book of Thoth, said Etteilla, contained the sciences, religion, oracle, and universal medicine of the Ancient Magi of Egypt.

He was echoing a thought popularized by Antoine Court de Gébelin (1725 – 1784), a Parisian Freemason who reconstructed tarot history as originating from Egyptian high priests, whose secrets were then transmitted to the popes of the Holy Roman Empire, who then transmitted those secrets to France during the Avignon Papacy, between 1309 and 1376. Court de Gebelin presented a theory that the cards were pages or leaves from a magical text written by ancient Egyptian priests, disguised as a pack of playing cards so that the leaves could escape the flames that destroyed the Library of Alexandria. These hieroglyphs conveyed morality, politics, philosophy, and the history of civilizations.

In 1781, Le Comte de Mellet writes an article in a volume of Court de Gebelin’s Le Monde Primitif, describing the tarot as The Book of Thoth. This Book of Thoth purportedly revealed the origins of the universe. Comte de Mellet asserted that the word “tarot” was derived from the Egyptian “Ta-Rosh,” a reference to scientific doctrine and Thoth (syncretized with the god Mercury), also known as Hermes Trismegistus.

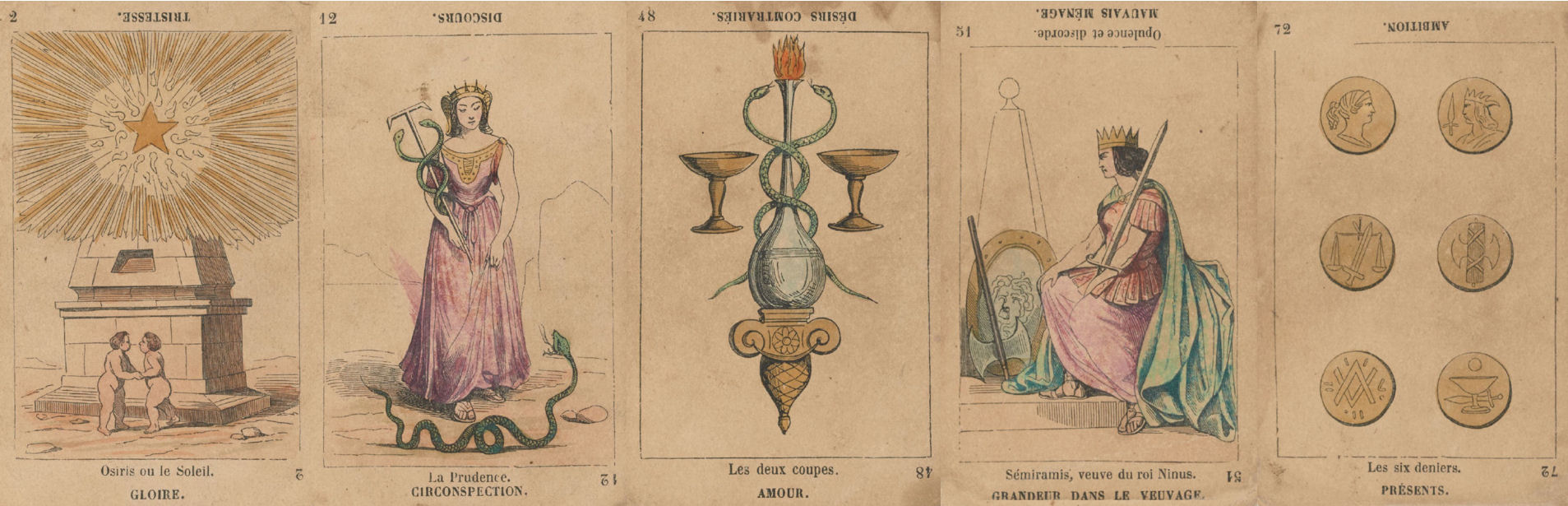

After Antoine Court de Gebelin and the Comte de Mellet asserted that the French and Italian tarots were encoded transmissions of the Egyptian Book of Thoth, Etteilla expanded upon that premise to create his own Hermetic-based divination deck, which he touted as a rectification or restoration of the “true” sequence of the Arcana.

In the 1783 – 1785 Manière de se récréer avec le jeu de cartes nommées Tarots (How to Entertain Oneself with the Deck of Cards Called Tarot), Etteilla claimed that the tarot was first inscribed in a fire temple in Memphis. In an effort to restore the tarot architecture back to the original Book of Thoth, he would re-order the tarot trumps in accordance with revelations found in the Divine Pymander, which purportedly preserved that “true” sequence first authored by the magi.

In 1788, at the age of 50, Etteilla commissions Pierre-Francois Basan to create a set of uncolored engraved sheets that became the first edition of his Grand Etteilla Tarot. To fund the printing of his deck, he campaigned around town to collect the money he needed to pay for its production (the first Kickstarter?). Watercolor was later applied to those engravings for a colored edition.

Etteilla and his collaborator cobbled together pre-existing engravings pulled from various sources to create the illustrations. Wait, whut… you mean like an 18th century mixed media collage deck? =P

Then in 1789, Etteilla applies for a general patent to print his deck, calling it the Book of Thoth, the Tarot of the Egyptians. “M. Etteilla, Professeur d’Algebre” at 48 Rue de l’Oseille, described his French edition of Livre de Thot (Book of Thoth) as revealing the theory and practice of ancient Egyptian magic through the tarot.

Etteilla seemed to have been quite business savvy, attending print shop conferences in Strasbourg to learn more about the trade. (At the time, the best quality tarot cards were purportedly printed in Strasbourg.) And had the acumen to apply for licenses and patents to further his tarot and magic school business.

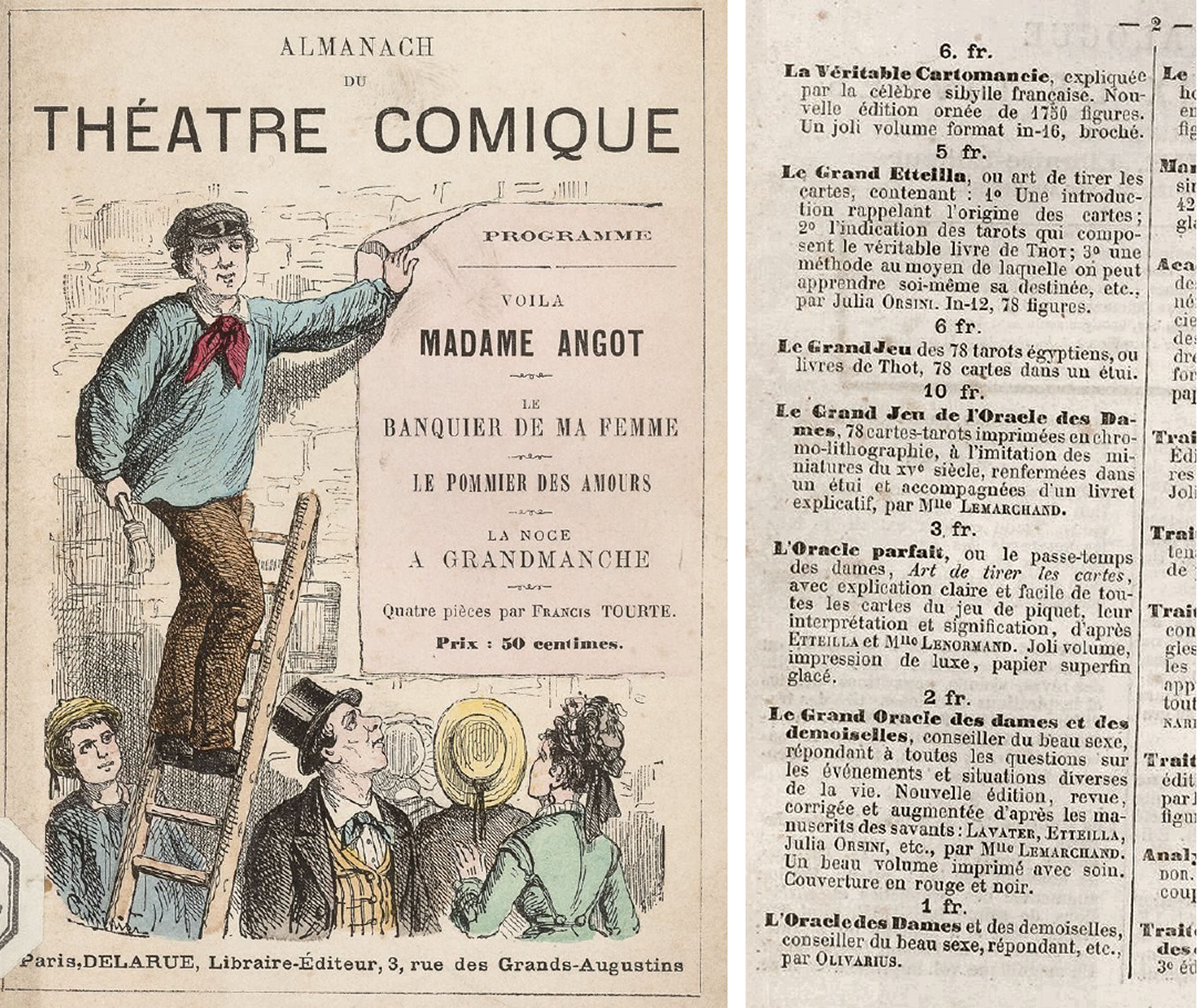

He wrote and self-published books on tarot, astrology, magic, and cartomancy. And yes, he put out ads for those products, too, along with ads for his magic school and tarot courses. He had a weekly newsletter that served to both market his wares and services and also position himself as an expert in the field of occult sciences.

Etteilla aggressively marketed his school in local papers. He was one of the early promoters of card reading as a professional activity—that’s right, he taught people how to “go pro” with tarot. Many of the pupils who took classes from him went on to become tarot and astrology teachers at his school. Etteilla is credited as one of the early influencers who integrated a system of magical theory into the tarot.

He effectively branded himself by advertising the major predictions he got right, claiming that his cards predicted the French Revolution and the Storming of the Bastille. He flooded the Parisian marketplace with his tarot books and positioned himself as an occultist with forty years of study in Egyptian magic.

“It is not as a sorcerer that I divine… but as a philosopher that I prognosticate. . . . It is by fixing the cause that moves you, and the incontestable effect that must result from it… that I prognosticate what will happen to you.”

– Etteilla’s “Épître à Monsieur Court de Gébelin” (1784)

The extent of his advertising and marketing efforts stirred objections from more “serious” occultists. Etteilla was, in short, over-commercializing the tarot… or so went the critique.

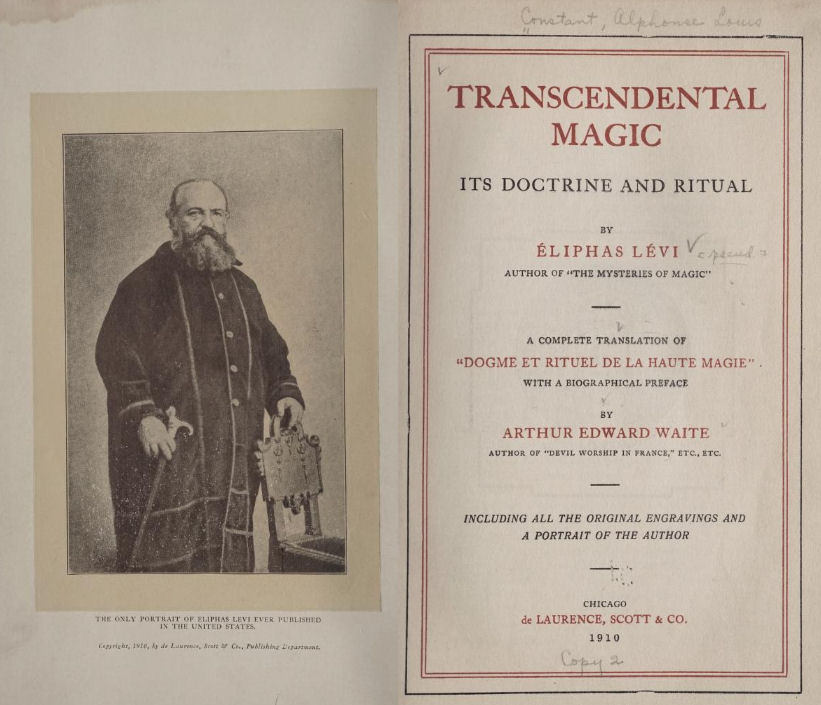

Eliphas Levi expressed contempt for the way Etteilla popularized the tarot for fortune-telling. Etteilla was peddling “wearisome and barbarous” (Levi’s words) forms of low magic, as opposed to Levi’s proposition of the tarot as a sacred tool for transcendental high magic. Levi further describes Etteilla as almost having found the secrets but “misplaced the keys.”

In Pictorial Key, Waite described Etteilla as “the illiterate but zealous adventurer, Alliette, . . . that perruquier (wig maker) who took himself with high seriousness and posed rather as a priest of the occult sciences.” In Aleister Crowley’s The Book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians (1944), Crowly refers to Etteilla as “the grotesque barber Alliette,” dismissing his contributions to tarot.

In An Encyclopedia of Occultism (1920), occult scholar James Lewis Thomas Chalmers Spence, or Lewis Spence (1874 – 1955), described Etteilla’s work with the following:

“By profession he was a barber . . . but on entering upon his occult labors he read it backwards. . . . He had but little education, and was ill acquainted with the philosophy of the Initiates. Nevertheless he possessed a profound intuition, and, if we believe Eliphas Levi, came very near to unveiling the secrets of the Tarot. . . . [Etteilla] claimed to have revised the Book of Thot, but in reality he spoilt it, regarding as blunders certain cards whose meaning he had failed to grasp. . . . It has also been said of him that he had degraded the science of the Tarot into the cartomancy, or fortune-telling by cards, of the vulgar.”

The constant jabbing references to Etteilla as a hairdresser or barber imply a condescension toward Etteilla’s scholarship, treating him as mere entertainment, rather than studied mysticism. (Compare to how Etteilla described himself– as a “Professeur d’Algebre,” or Professor of Algebra).

Surrealist painter, historian, and occultist Kurt Seligmann (1900 – 1962) also reiterated Etteilla’s vocation as a “wig-maker” and “vainglorious hairdresser” who “embellished” the tarot “according to the taste of his epoch” and “gave them some new and rather unorthodox attributes.” Writes Seligmann:

“He changed the sequence of the leaves, discarding some and adding new ones which he declared were the oldest images, lost during the peregrinations of the game from Egypt to Europe. In brief, he confused everything completely.” [From The History of Magic (1948) by Kurt Seligmann]

Despite the criticisms, it’s undeniable that Etteilla’s contributions to tarot were foundational and transformative. His work bridges esoteric symbolism and public accessibility, and it was his popularity that allowed a niche craft like the tarot to gain broader awareness.

True to form, Etteilla was also the subject of tarot community drama, most notably the rivalry with a former pupil of his, d’Odoucet, where both parties resorted to published name-calling, though after Etteilla’s death, d’Odoucet went on to commercialize off of Etteilla’s legacy, so the apple of a student didn’t fall far from the tree of a teacher.

The man was also fearless with his commentary on politics, leaning progressive. He supported the Revolution. He called for the abolishing of taxes on playing cards (or at least divinatory ones like his Book of Thoth tarot). He was against the death penalty.

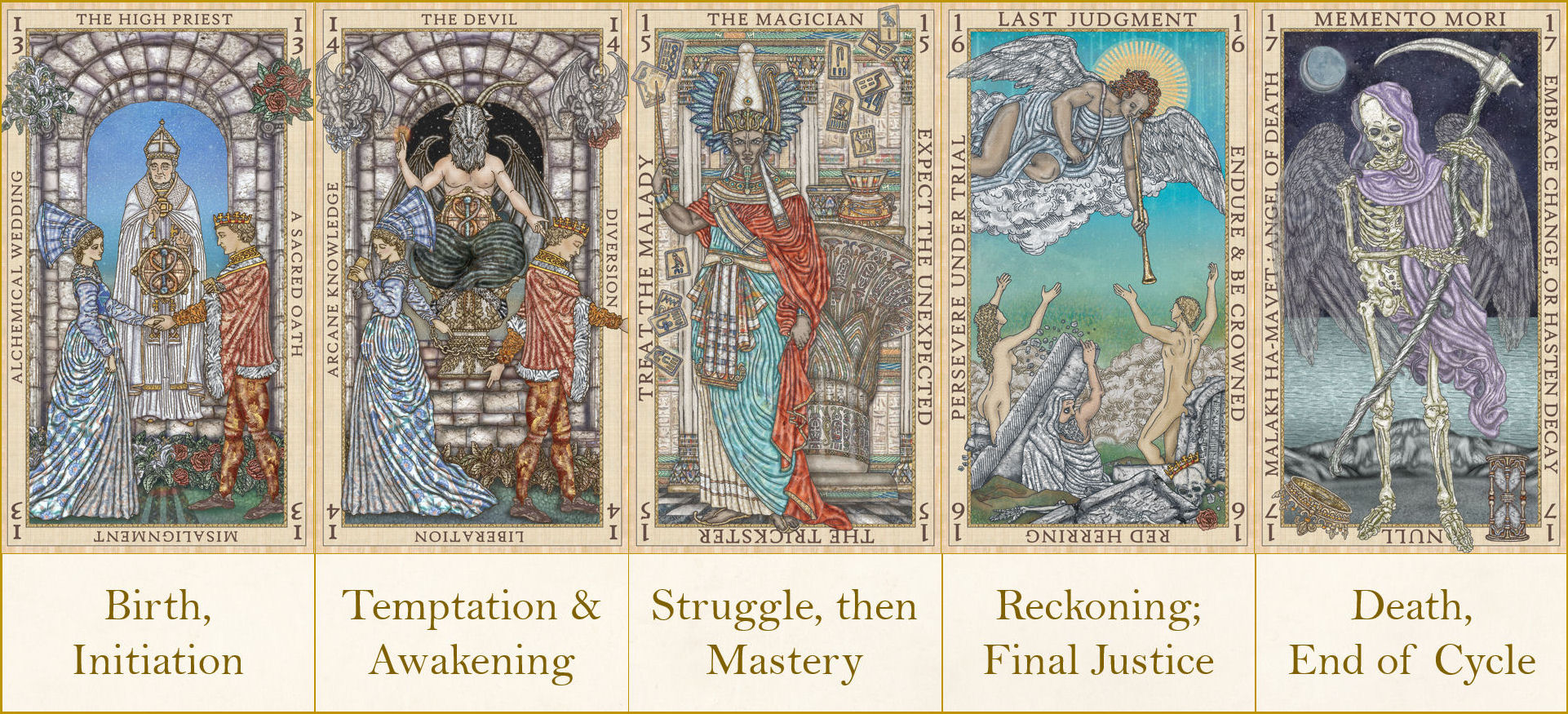

His unapologetic flair for self-promotion was matched by an equally audacious re-imagining of the tarot itself. He was not content to merely teach existing systems, but sought to innovate and transcend. Drawing from astrology, Hermeticism, and his own interpretations of Egyptian mythos, Etteilla developed an entirely new esoteric structure for the cards, one that challenged the familiar ordering. The Grand Etteilla Tarot, as it came to be known, was designed from the ground up for divination, embedding astrological correspondences, planetary influences, and life-cycle archetypes.

Cards 1 to 12 correspond with the twelve zodiac signs. And so instead of the more familiar Justice card being associated with Libra, here in Etteilla’s system, it’s Card 7, The Birds and The Fishes, and instead of The Lovers card associated with Gemini, here, it’s Card 3, The Plants, with imagery reminiscent of the more conventional tarot Moon card. Aquarius in this system is associated with Fortitude, instead of the more commonly associated Star card.

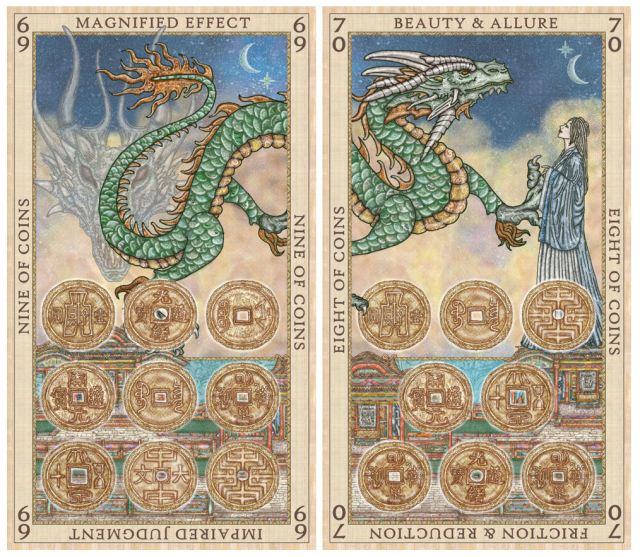

The Sacred Seven planets plus the lunar nodes and Hermetic Lot of Fortune correspond to the pips in the suit of Coins, where the Ace of Coins corresponds with the Sun, Two of Coins to Mercury, Three of Coins to Venus, and Four of Coins to the Moon, etc.

Cards 13 to 17 represent the human chain from birth to death, or five stages of the human life cycle– initiation into society (Card 13), rebellious adolescent youth (14), adulthood (15), maturation (16), and death (17).

While Etteilla’s system of esoteric tarot lost popularity over the centuries, it is nonetheless considered the first tarot deck created fully for the intention of divination and symbolic use, rather than games.

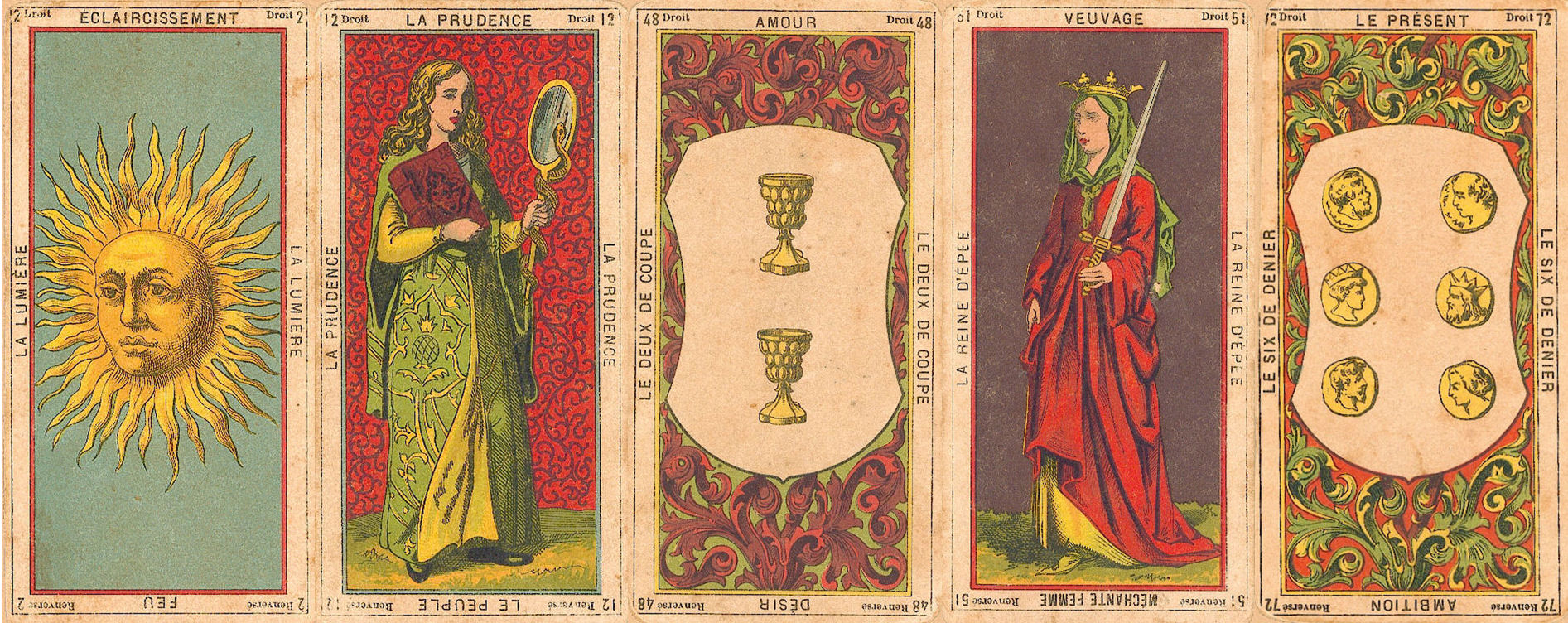

The Grand Etteilla Tarot diverged from the traditional Tarot de Marseille ordering, iconography, thematic symbolism, and meanings were assigned to the cards, both upright and reversed, often running in opposition to the popularized card meanings tarot readers today are used to.

As seen in the critiques of his work, Etteilla’s re-ordering of the Major Arcana and some of his assigned card meanings were frequently challenged and even mocked. In 1888, MacGregor Mathers wrote about Etteilla, “The worst of Etteilla’s system is that he so completely destroys the meanings of the Keys in his attempted rearrangement of them, as to make them practically useless for higher occult purposes.”

Said Waite, “The little books of Etteilla are proof positive that he did not know even his own language; when in the course of time he produced a reformed Tarot, even those who think of him tenderly admit that he spoiled its symbolism.”

The criticisms notwithstanding, Etteilla’s bravado attracted attention. He became known as Le Célèbre Etteilla—the Famous Etteilla. “Disciples and rivals grew up and thronged around him,” remarked P.R.S. Foli (Fortune Telling by Cards, 1915).

Etteilla in the 21st century would absolutely be doing livestream pick-a-card readings on your twin flame and marketing online tarot courses. He may even be offering tarot certification. Would anyone be surprised if he launched crowdfunded campaigns for his fortune-telling decks? At the center of major controversies that flared up in the tarot community would be Etteilla, either having started it or helping to fan its flames as he writes up his own colorful commentaries.

18th century Etteilla published a weekly pamphlet through his New School of Magic, so of course a 21st century Etteilla would be e-mailing out weekly newsletters that cover everything from his opinion on current affairs and politics to psychic predictions, self-congratulatory commentary on the accuracy of his past predictions, and more advertisements for his tarot courses and cartomancy readings.

Etteilla first began his cartomancy design ventures by devising a 33-card divination deck referred to as the Petit Etteilla. In 1789 he brings to market a full 78-card deck, the Grand Etteilla. This original iteration engraved by Pierre-François Basan is dubbed the “Etteilla I.”

The Etteilla tarots are numbered with Arabic numerals rather than the Roman numerals that were more popular among European tarot card makers at the time. The Arabic numbering echoed the 18th century sentiment that the Egyptian tarot was spread to Spain by way of Arab conquests in Southern and Eastern Europe, then brought to Italy by way of the Romans.

Around 1826, an edition of Etteilla I is revised with symbolic references to Freemasonry, later published as the Grand Etteilla Tarot by the publishing house Grimaud.

In 1838, Simon François Bloquel, a French printmaker, would publish a second iteration of the deck, called the Great Book of Thoth, now referred to as “Etteilla II” to distinguish it from Etteilla’s original version.

The third notable version published in 1865, illustrated in a Neo-Gothic style, called the Grand jeu de l’Oracles des Dames is what we refer to as “Etteilla III.”

Prior to Etteilla III, in 1843 there was a version of the Etteilla called the Princess Tarot, illustrated with a more overt Egyptian aesthetic blended with Greco-Roman iconography.

SIDEBAR | For free downloads of the historical Etteilla decks and related paraphernalia, check out the page ETTEILLA TAROT DOWNLOADS.

When the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn rose to prominence in the late 19th century, their approach to the tarot set a new precedent, overturning the Etteilla and, at least for most of the English-speaking world, cast the older Etteilla decks into obscurity.

Yet the body of tarot divination work and the integration of occult philosophy into tarot is duly credited to Etteilla, alongside Antoine Court de Gebelin and the Comte de Mellet.

Historians trace the game of tarot to Renaissance Italy, but it was 18th century France that gave the cards its occult interpretation. It was the work of French occultists that crystallized the characterization of tarot as a book of revelations on cosmogony. Etteilla is also credited as one of the early tarotists to espouse reading with reversals.

My take on the Etteilla tarot, as an illustrator and as a modern-day tarot reader, is an homage to the 18th century French popularization of embedding occult philosophy in the tarot.

![]()

lEARN mORE aBOUT bENEBELL’S

TAROT OF THOTH-HERMES

![]()