Maybe I’m Not a “Witch.” Maybe We’re Excluded for a Reason.

There was a fun witchy banner I scrolled upon with this happy, inspiring message of “Pagans and Witches Unite!” It then featured Stregheria, Feri, Cultus Sabbati, Luciferian, Haitian Vodou, Santeria (Lukumi), Palo Mayombe, Wicca, and then a catch-all “Indigenous Shamanic Paths.”

No special call-out to Asians?

And by “Asian” I really do mean continental, islander, north, south, east, west, there was NO representation there at all. For the largest most populated continent in the world, making up more than half the global population of magical traditions and practices, people just decided to tuck all of that under “Other”?

It seems like Asian magical traditions are always getting left out.

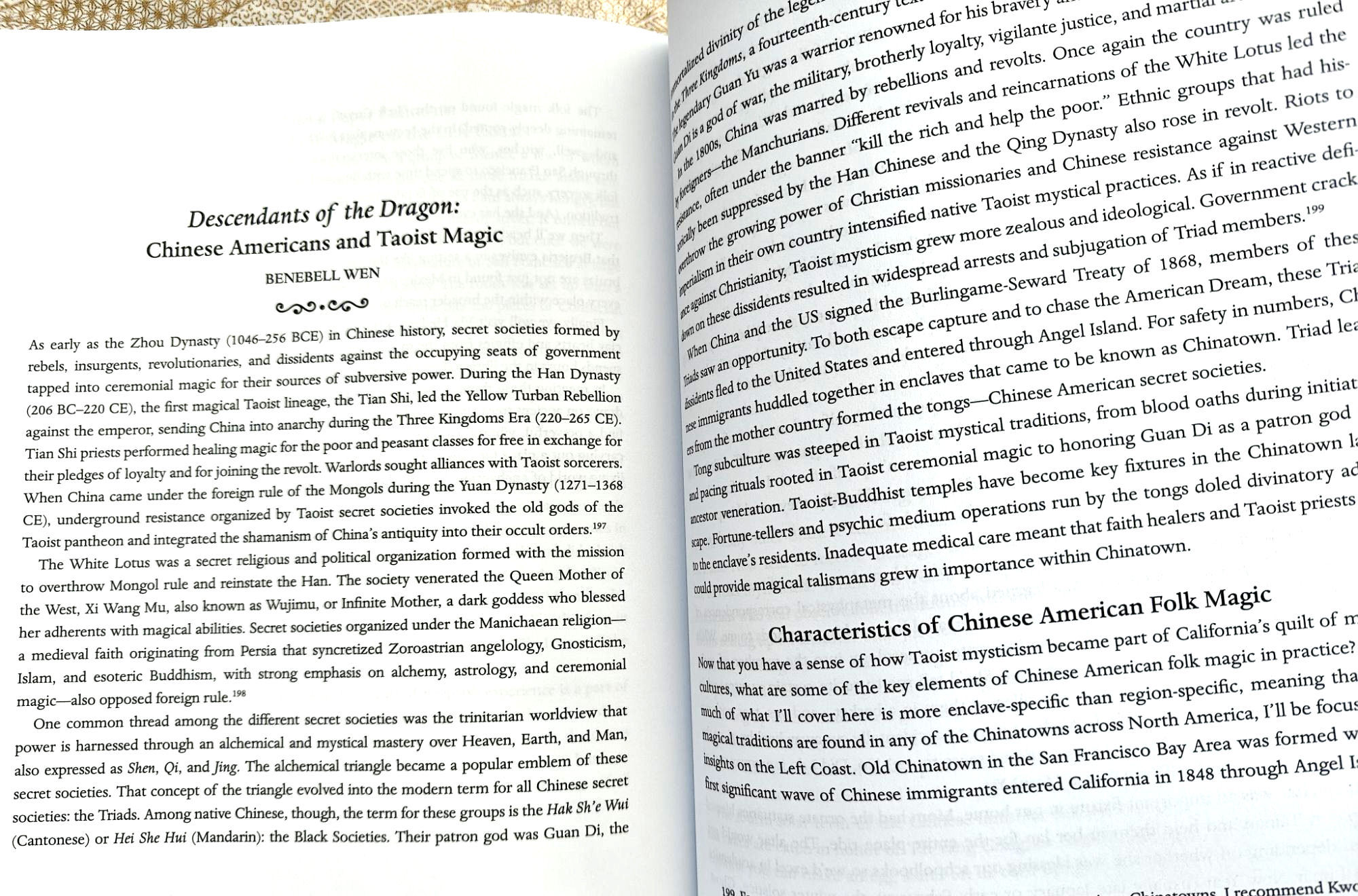

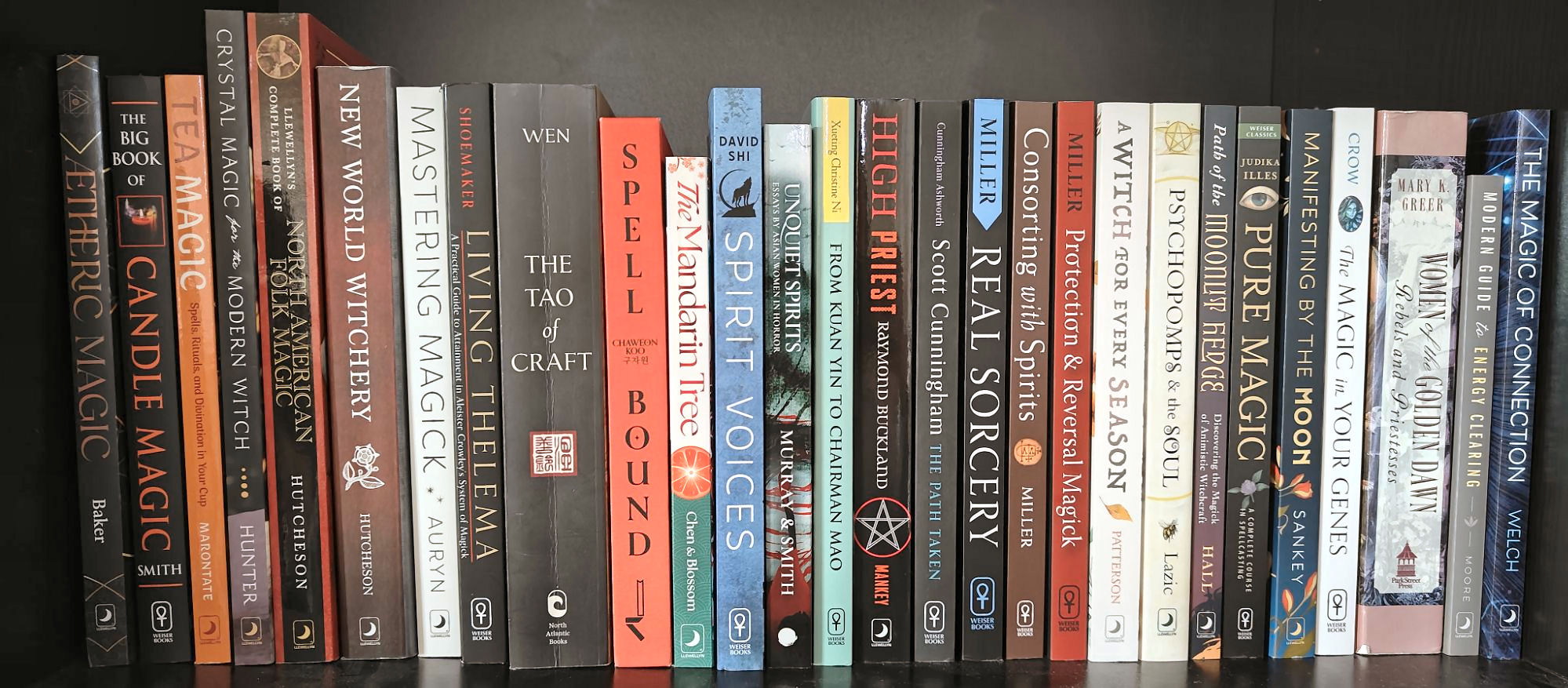

Though quick shout-out to Cory Hutcheson and Mat Auryn, who both included Taoist traditions, Cory in North American Folk Magic and Mat in Mastering Magick.

As an Asian American, I’ve spent decades trying to find ways to include or have included diasporic Asian folk magic and mystical traditions in Western pagan, occult, witchcraft, and magical spaces.

And it’s because I keep hoping one day I’ll scroll upon a fun witchy banner that finally remembers to include Asia. Literally any part of Asia getting included would be an exciting win.

In recent years there’s been many emerging voices in the AAPI magical space. Coven of the East: Reimagining Asian Women’s Magical Histories, edited by Angela Yuriko Smith and Pauline Chow is an incredible anthology of 22 writers exploring Asian magical traditions, folklore, ancestral wisdom, and mysticism. Such an anthology is pioneering and significant, yet didn’t seem to receive much visibility in the broader pagan and witchcraft community that comparable works often do. And in a somewhat tangent genre was Unquiet Spirits, an Asian anthology of narrative essays on personal experiences with the magical and mystical. (Btw, I contributed nonfiction essays to both, and in Unquiet Spirits, you’ll find a true ghost/demon family history story from me.)

We’ve also had fresh, new perspectives on magical practice at the intersection of our hyphenated experience, from Chaweon Koo’s Spell Bound: A New Witch’s Guide to Crafting the Future to Pamela Chen and Samantha Blossom’s The Mandarin Tree: Manifest Joy, Luck, and Magic with Two Asian American Mystics, alongside more focused spiritual expositions, like David Shi’s Spirit Voices: The Mysteries and Magic of North Asian Shamanism. Zachary Lui, a practitioner of Buddhist ritual magic and shamanism, has also been putting forth lots of really cool work for North American pagan and witchcraft communities.

Mudang Jenn, who I’m really finding myself liking a lot, has a strong social media presence and is well recognized within the Asian American arts community. Shaman Seo (Seo Choi) helped bring to life an incredibly important and historic memoir, Kim Keum-Hwa’s I Have Come on a Lonely Path: Memoir of a Shaman.

… Though I guess perhaps Korean and North Asian shamanism were included in that inspirational banner under “Indigenous Shamanic Paths.” …

I’ve also come across some rising young stars over on WitchTok, like Orion @thatasianwitch, an Asian folk practitioner and who talks a lot about Asian folk magic, and Emma Peng @emmapeng0619, who has a broader scope of content, but posts a lot of great stuff on Chinese witchcraft.

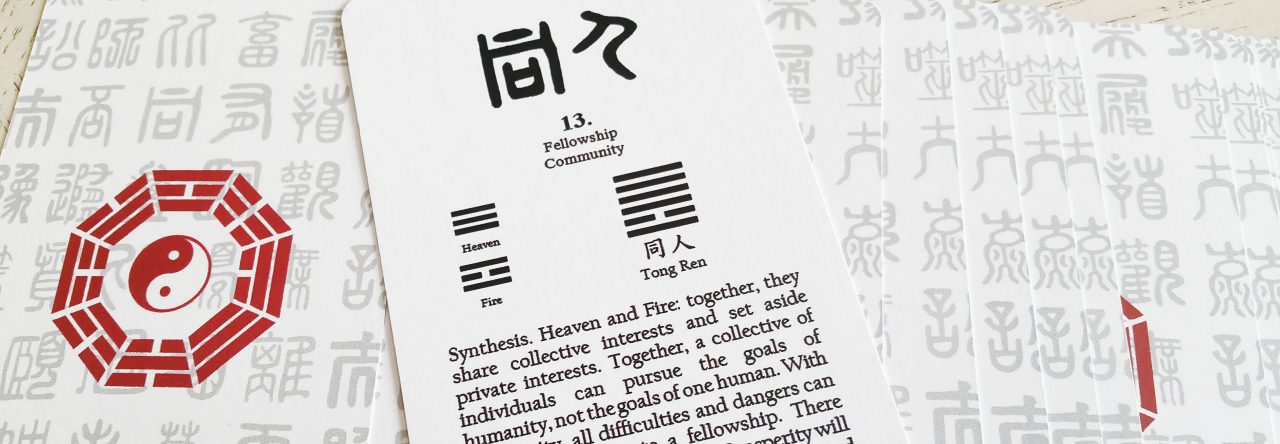

On the other hand, sometimes Asian holistic health and wellness practices with this tangent dotted line to folk magic and Taoist or Buddhist mysticism (think: Traditional Chinese Medicine, feng shui, tai chi or qigong, BaZi and Chinese astrology, Taoist shamanism, Taoist alchemy, esoteric and/or tantric Buddhism) is its own standalone Thing. You’ll even notice those types of books tend to get published by a different cluster of publishing houses, and aren’t getting picked up by Llewellyn, Weiser, and so forth. I’m thinking of the Eva Wong, Sarah Jane Ho, and Mantak Chia types. So, what I’m seeing here is, what would be stronger united under one category is getting fractured into two, one half leaning toward the pagan/witchcraft camp and the other leaning toward the holistic health and wellness camp. Am I even making any sense?

Now admittedly, here’s the thing.

If we want to put on a more serious hat, be that academic or the seasoned practitioner, and we’re going to be splitting hairs, yeah, a strong argument can be made that, insofar as the East Asian esoteric traditions I am knowledgeable in, categorizing them under paganism or witchcraft aren’t good fits.

When we consider how the word “witch” is used culturally in the Americas, there is no really good direct translation in Chinese, and as I understand, same goes for Japanese, Korean, Tagalog, and Vietnamese. In many of the Asian magical traditions, the cultural concept of “witch” is too vague that there is no one word for it; rather, all the various subset practices we might associate with “witch” are standalone identities. Our common terms break it down at the subset practice level: a word for someone who is a spirit medium entering trance states to engage with spirits of other realms; a word for someone who leads ceremonial rites and rituals (ceremonial magician-ish), a diviner or fortune-teller, an initiated priest or priestess in a clearly defined lineaged tradition, an alchemist (a term that can cover either practitioner of inner alchemy or outer alchemy).

From my firsthand observations, even if an Asian practitioner does all of the above in terms of magical practices, they will have specialized in one of them, and then they self-identify in that one specialty, such as “spirit medium,” even if in actual practice, they’re also doing fortune-telling and divination, folk (or faith) healing plus TCM, and crafting Fu talismans. Likewise, someone who specializes in feng shui will lead with that title, but in actual practice, are also doing natal astrology, BaZi readings, and exorcisms.

Not to get into a discussion on the Chinese term “wu 巫” again, because I’ve talked about it ad nauseum in dozens of places at this point, but in short reductionist summary, the term in modern cultural usage can mean shaman and it can also mean something close to the Western cultural concept of witch. The only problem with using “wu 巫” and witch synonymously is when used, in Chinese, in the context of witchcraft or sorcery, it is unequivocally culturally attributed to baneful magic, gu poison magic, hexing, and cursing, even though historically in Chinese traditions that was not the case, although Millennial and Gen Z Asian practitioners are reclaiming the term “巫” to mean something positive. (It’s messy and complicated.) The polarity to “wu 巫” interpreted as “witch” in older generations of practitioners was “xiangu 仙姑,” which very narrowly means using those same powers of the wu 巫 but benevolently, specifically implying spiritual lineage from Xiangu, the shaman-priestess among the Eight Immortals. Which then devolves into this debate over binary separations of good vs. evil, and you’re going to find Asian practitioners from varying generations on both sides of that fence adamant that their perspective is right and the other is wrong.

In an effort, here in the West, to find common ground and to be inclusive, I had always treated the term “witchcraft” as a catch-all that we might be able to use cross-culturally, to identify and explain a particular category of people that you find in nearly every community or society. After all, can’t we define witchcraft as an intentional, ritualistic, and often methodical use of sound as power (invocations, drums, etc.), script and symbols, herbs, elements such as fire and water, to wield unseen energy in accordance with will, often involving altered states of consciousness. It’s also an identity that’s marginal, referring to one who occupies liminal spaces.

And so, although fully conscious that it’s an imperfect catch-all moniker, in English, we pool all of those very different practitioner hats under one umbrella—paganism and witchcraft, witches and pagans.

Nature-based practice and pantheon of deities? Check. Longstanding traditions of spirit communication and trance states? Check. Mediumship and divination practices? Check, check. Spell-crafting, talismans, altars, ritual tools, comprehensive methodologies in baneful sorcery? All of the above. So we Asian American practitioners can call ourselves pagans? Yah sure why not.

But then the minute I’m in these pagan and witchcraft community spaces, immediately I realize, the energy imprints here are totally different. I don’t actually belong here. Perhaps they’ve kindly included me for, I dunno, diversity optics, but it feels as if I’m not here because attendees would actually be interested in my topics or that Asian folk traditions belong; I’m here to fill a quota.

Even when I get invited to a pagan conference where I feel a genuine warmth and welcome, it’s coming primarily from the organizers and the handful of people already familiar with me or my work prior to the conference. But once I wander out into the wild, it’s not that anyone is malicious or even insensitive, it’s that the difference is palpable. And genuinely, I don’t believe it’s intentional exclusion. It’s more like…like I said, I don’t belong here. I’ve been misclassified? Maybe I’m not a pagan, or a witch? Maybe there’s a fundamental misalignment that’s nobody’s fault?

Also, it’s hard to fight for inclusivity in Western pagan and witchcraft spaces when we Asian Americans can’t even put on a united front. We’re so busy feuding amongst ourselves, how the heck do we negotiate for visibility or a seat at that table? Like Asians creating blacklists of fellow Asians in semi-secret Discord groups accusing one another of not being legit shamans because blah blah blah, and so-and-so isn’t a real mudang/priest/shrine maiden. This person isn’t Asian enough to understand indigenous Asian folk practices; that person isn’t American enough to understand the identity politics and therefore labels we have to contend with. This fellow Asian is problematic; that fellow Asian practitioner is known for toxic behavior (important call-outs when they turn out to be real; except in a couple of instances, when you pull on the thread, it unravels to the true ulterior motive: business rivalry). “Pagans and Witches Unite…” Maybe I’m putting the cart before the horse, and maybe step one is “Asian Practitioners of Folk Traditions Unite.” Before we meet with the wider assembly of pagans and witches, we need to meet internally to heal generational and regional divides, arguments over lineage and legitimacy, and settle the squabbles over who is authentic and who isn’t.

Of course, there’s a reason unity is tough: so-called “Asian folk traditions” is by no means a monolith, and one facet of it compared to another facet is about as different as practices and philosophies can be. East Asia, Southeast Asia, West Asia, South Asia… we need to be sensitive to the diversity and differences, and yet also, we need some sort of shorthand, however imperfect, to be able to have conversations. We have our own internal diversity and inclusion complexities to resolve before we demand diversity and inclusion in the wider community. Which now makes me realize I’m kind of a hypocrite for critiquing that meme.

Do I think Asian folk traditions (disclaimer: shorthand being used) belong under the umbrella term of paganism so that we have some semblance of visibility when relevant social discourse is taking place? Are our regional folk magical practices considered “witchcraft”? Or do I think Asian folk traditions don’t belong because for all the Reasons, we’re not pagans or witches?

Ultimately, I think I land (at least as of this writing) in the position of “let’s just keep calling ourselves pagans and witches” because there’s enough commonality to work with, and it’s our most viable route to inclusivity and representation. We’re demeaned enough by mainstream society, we shouldn’t be doing it amongst ourselves.

And hopefully if the AAPI community keeps showing up, one day one of these fun memes will remember to specifically call out Asian folk magic.

![]()

🔥🐴!

I hear so much of the 丙午 year’s sentiment in this writing.🥹

As the last time that Year Pillar happened was the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, I find the gravitas of what you said so very important in its timely expression.

Beautifully thoughtful and deeply meaningful traditions deserve to be elevated– not just marginally preserved as some abstract footnotes. They live on vibrantly, and should shine brightly for all the world to see, recognize, and resonate with as one.

Thank you. =O)

LikeLike

Warning: This comment will feel out of place! (Although I’ll be careful with the wording and see if I can weave it into this discussion as a side note and cross my fingers and toes and hope for a reply). Is there such a thing as a descent into madness associated with any of the above mentioned traditions if, let’s say if one were to try it alone without guidance or community?

LikeLike